Programming involves a particular flavour of problem solving. If you're a beginner trying to get better at it, an educator teaching beginners, or just someone who enjoys thinking about thinking, then I may have just the book for you: Think Like a Programmer from No Starch Press.

This book is, as its subtitle promises, an introduction to creative problem solving. It starts with a chapter on general problem solving techniques such as breaking problems into smaller pieces and looking for answers in what you already know. It then devotes a chapter to solving non-programming problems with code. After that, most of the book covers some of the basic problem types all programmers encounter, including arrays, dynamic memory, class design, recursion, and code reuse. The last chapter summarizes general techniques for thinking like a programmer.

I read this book as someone interested in computer science education, particularly for beginners. But despite the fact that I'm an experienced programmer of ten years, I actually enjoyed readinf about things I already know how to do. It ended up being an interesting exercise in thinking about thinking, and it brought my attention back to some of the details about programming that I now take for granted.

The author has an easy-to-understand, approachable, discussion-based style of writing. There is a good progression through topics — as a course instructor, you could certainly mirror the flow of the book even if you didn't want to use it as the official text. The numerous diagrams are clear and genuinely useful. I also love that good programming practices are embedded in the discussion, and that many other aspects of CS (for example, data structures) make an appearance in a natural way.

One of the chapters I was most curious about is the one on recursion, given how difficult this topic can be to teach. I liked that this topic was introduced with a detailed real-life example of head and tail recursion. I'm not sure if I was never explicitly taught these concepts or if I've come to take them for granted by now, but I have at the very least not thought about the difference in a long time. I appreciated bringing these ideas back to my conscious mind, and felt like the discussion should be helpful to beginners. I also liked the suggestion to solve problems as if there was no recursion, and to just trust the recursive call to do its thing. (Incidentally, you can read this chapter online, where it is offered as a sample.)

There were a few things I didn't like as much, such as the unnecessarily long paragraphs. I also thought some of the sample problems were cliched and rather dull (how many of us actually care about keeping track of student records?). Each chapter begins with a very fast review of relevant C++ syntax, and while I understand why this is done, I find it ends up being too sparse to be useful to anyone who actually needs it.

Probably the thing I struggle with the most is the choice of C++. I actually think C++ is a reasonable early language for computer science majors (at least in terms of what's currently available), and the rationale for choosing it for the book is sound. However, I don't really know of many post-secondary programs that teach C++ first. The problem is that the book would become a lot less relevant after the first course or two in a good CS program since the concepts will already have been covered, but it's difficult to make use of it unless you already know some C++.

Nonetheless, given to a new programmer at the right time, I think the book has the potential to be very valuable. It comes highly recommended in my mind.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Proof Overtime Is Bad

I am against overtime. I do as little of it as possible. And now I have proof that this philosophy actually makes sense!

Before any potential future employers find this and take my resume off the pile, let me explain. Knowing how long I can work before getting tired is important to me. If I go too long, then I'm likely to just make things worse. Plus, if I know I only have a set amount of time to get things done, I can focus better - there is no later. The standard 8 or 9 hour day seems to work perfectly well for me.

That's not to say that I'm not willing to put in some extra time around a deadline, of course. I have stayed late a few times during my co-op terms and I've worked into the evening on school stuff more than once (though I've only ever done one all-nighter, and it wasn't even strictly necessary). I just ensure this is very much the exception and not the norm.

So, back to this proof I mentioned. The IGDA has a great article on why perpetual crunch modes just don't work. Most other industries started figuring this out 100 years ago (hence why the 40 hour work week is fairly standard). Research literally proves that after a certain number of hours worked in a single week, output goes down when compared to a more regular work week. Working more just doesn't pay.

High tech can be a brutal field when it comes to overtime expectations. My strategy? Don't make working longer a precedent. If you do, then that amount of work will be expected of you. But, of course, the more you work long hours, the less you'll do over time, making you want to work longer to make up for it, making you accomplish less... and so it goes...

The Sleeping Geek Kitten - Angers - / Nathonline-Beta

Before any potential future employers find this and take my resume off the pile, let me explain. Knowing how long I can work before getting tired is important to me. If I go too long, then I'm likely to just make things worse. Plus, if I know I only have a set amount of time to get things done, I can focus better - there is no later. The standard 8 or 9 hour day seems to work perfectly well for me.

That's not to say that I'm not willing to put in some extra time around a deadline, of course. I have stayed late a few times during my co-op terms and I've worked into the evening on school stuff more than once (though I've only ever done one all-nighter, and it wasn't even strictly necessary). I just ensure this is very much the exception and not the norm.

So, back to this proof I mentioned. The IGDA has a great article on why perpetual crunch modes just don't work. Most other industries started figuring this out 100 years ago (hence why the 40 hour work week is fairly standard). Research literally proves that after a certain number of hours worked in a single week, output goes down when compared to a more regular work week. Working more just doesn't pay.

High tech can be a brutal field when it comes to overtime expectations. My strategy? Don't make working longer a precedent. If you do, then that amount of work will be expected of you. But, of course, the more you work long hours, the less you'll do over time, making you want to work longer to make up for it, making you accomplish less... and so it goes...

Monday, November 26, 2012

Resources for Testing Game Story Ideas

I will soon be trying out simple nonlinear narrative ideas for my thesis research, and wanted to find (freely available) tools that will make doing so much easier. Here are a few, some of which are great for beginners and non-programmers. (Know of any other great tools? Let me know in the comments!)

inklewriter

If you want to create branching stories quickly and easily, this free graphical tool might just be for you. It's not likely to be useful for me without access to its source code, but non-programmers should have some fun with it.

Ren'Py

This is how Ren'Py describes itself:

Fabula

As per the Fabula website:

Orx

According to the Orx project site:

inklewriter

If you want to create branching stories quickly and easily, this free graphical tool might just be for you. It's not likely to be useful for me without access to its source code, but non-programmers should have some fun with it.

Ren'Py

This is how Ren'Py describes itself:

Ren'Py is a visual novel engine that helps you use words, images, and sounds to tell stories with the computer. These can be both visual novels and life simulation games. The easy to learn script language allows you to efficiently write large visual novels, while its Python scripting is enough for complex simulation games.I like that beginners can use its simple scripting language to create interesting stories, and that I will be able to use Python to make more sophisticated games. This is probably the first tool I'm going to download and try since it should be really fast to get going on the simplest of ideas.

Fabula

As per the Fabula website:

Fabula is an Open Source Python Game Engine suitable for adventure, role-playing and strategy games and digital interactive storytelling. Fabula can be used as a library to develop your own games. As an alternative, you can use the Pygame-based graphical editor and the default game engine that come with fabula.With this tool, you get into programmer's territory, but still get a lot for free. I like that the engine was designed with storytelling in mind, and that like Ren'Py it uses Python, which should make it fairly easy to work with. I will likely give this one a try early on as well.

Orx

According to the Orx project site:

Orx is an open source, portable, lightweight, plugin-based, data-driven and extremely easy to use 2D-oriented game engine. It has been created to allow fast creation of games and prototypes.The reason I include this project is because I think 2D is the way to go to test story ideas, and such an engine would make creating a 2D game much easier. If the other tools aren't flexible enough to customize things as much as desired, then this might be the way to go (assuming you understand C/C++ programming). I probably won't use this one right away since I don't need the power, but I have a feeling it could come in handy later on.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Things I Like About Python

Back in May I wrote a popular post about which was a better beginners language: Processing or Python. Although I concluded that Processing was better for the audiences I tend to have in mind (that is, nontechnical members of the general public), that doesn't mean I think Python is a bad language.

I finally had the opportunity to use Python for my own project. I have been making a simple iOS QR code scavenger hunt / story game as a (very) side project for a while now, and am trying to give it the final push to completion. The game is defined in a plist file. I wanted to generate the QR codes automatically from the data in that plist. I also wanted to arrange the generated images into contact sheets with the text associated with each code written underneath. I figured this was the perfect opportunity to use Python for a real purpose instead of just as a teaching language.

The very best thing about Python is the fact that no matter what singular unit of work you need to do, you can almost always find freely available code online that does it. QR generator? Check. Contact sheet creation? Check. Help with the imaging library, including drawing text? Check. Put the pieces together and do some customization to suit my purposes, and I was off to the races.

I also like the 'scriptiness' of the language. I felt that I didn't need to work hard to make robust and reusable code. So long as it worked for my purpose here, that was good enough. This is a rare feeling for me. I usually feel compelled to make the code as general and 'nice' as possible. I loved being able to do what I wanted quickly and not worrying about what the result looked like.

But that's sort of a downside, too. When I stepped back to look at the code from a beginner's perspective, I noted how messy and likely difficult to understand it had become. I remember reading that Python inherently helped developers write good code (thanks to, for example, indentation to signify blocks of code). But this experience made me believe the opposite - it's so easy to write fast code that it can quickly end up being kind of ugly.

I also had a heck of a time getting everything set up on my Macbook. Python comes installed on OSX, but it's usually kind of old. So I downloaded and installed Python 3. After wrestling with the OS to get it to actually use that version for most Python-related things, I quickly found that the libraries I was trying to use didn't really work with this version. After several hours I ended up reverting back to the newest release of version 2. If I was a beginner trying to accomplish some relatively simple task, I would have been turned off the whole thing pretty quickly, if I even understood how to set up the environment in the first place (and I doubt much of the general public would, given how much time you are likely to spend at the command line).

So, all in all, I really like Python for my own purposes as an experienced programmer. But I'm still favouring Processing (or, even better, something like Scratch or some not-yet-existing language theorized by Bret Victor) as a beginner language. I could see Python being really handy once the basics are taught and some confidence is built, but I am still fairly sure I wouldn't want to begin with it if I had a choice.

I finally had the opportunity to use Python for my own project. I have been making a simple iOS QR code scavenger hunt / story game as a (very) side project for a while now, and am trying to give it the final push to completion. The game is defined in a plist file. I wanted to generate the QR codes automatically from the data in that plist. I also wanted to arrange the generated images into contact sheets with the text associated with each code written underneath. I figured this was the perfect opportunity to use Python for a real purpose instead of just as a teaching language.

The very best thing about Python is the fact that no matter what singular unit of work you need to do, you can almost always find freely available code online that does it. QR generator? Check. Contact sheet creation? Check. Help with the imaging library, including drawing text? Check. Put the pieces together and do some customization to suit my purposes, and I was off to the races.

I also like the 'scriptiness' of the language. I felt that I didn't need to work hard to make robust and reusable code. So long as it worked for my purpose here, that was good enough. This is a rare feeling for me. I usually feel compelled to make the code as general and 'nice' as possible. I loved being able to do what I wanted quickly and not worrying about what the result looked like.

But that's sort of a downside, too. When I stepped back to look at the code from a beginner's perspective, I noted how messy and likely difficult to understand it had become. I remember reading that Python inherently helped developers write good code (thanks to, for example, indentation to signify blocks of code). But this experience made me believe the opposite - it's so easy to write fast code that it can quickly end up being kind of ugly.

I also had a heck of a time getting everything set up on my Macbook. Python comes installed on OSX, but it's usually kind of old. So I downloaded and installed Python 3. After wrestling with the OS to get it to actually use that version for most Python-related things, I quickly found that the libraries I was trying to use didn't really work with this version. After several hours I ended up reverting back to the newest release of version 2. If I was a beginner trying to accomplish some relatively simple task, I would have been turned off the whole thing pretty quickly, if I even understood how to set up the environment in the first place (and I doubt much of the general public would, given how much time you are likely to spend at the command line).

So, all in all, I really like Python for my own purposes as an experienced programmer. But I'm still favouring Processing (or, even better, something like Scratch or some not-yet-existing language theorized by Bret Victor) as a beginner language. I could see Python being really handy once the basics are taught and some confidence is built, but I am still fairly sure I wouldn't want to begin with it if I had a choice.

Monday, November 12, 2012

Indie Game: The Movie

I am very grateful that I will (hopefully) be lucky enough to see my vision for my Gram's House game developed professionally with research grants. After watching Indie Game: The Movie, this sentiment has only increased. Though the documentary only presents one experience of independent game production, it's not an experience I particularly want to have.

I thought that this documentary was really well done. The filmmakers did a great job of finding a good story with tension and drama in the development process. I felt such relief when good things finally happened to each of them.

The elation experienced particularly by the Super Meat Boy creators got me thinking: what happens to those who spend a few hellish years trying to finish their masterpiece, but end up with little to show for it? I wonder how often the risks pay off? I'm sure not everyone drops everything to work on their game, and even those that do probably don't always forego any sort of life balance to do it. But I would not want to see anyone experience risking everything and losing.

Of course, great success doesn't always bring happiness. Braid's creator was shown to be fairly (even deeply) disappointed even after his game broke indie records. People loved his game, but they didn't get it. The reviews focused on superficial mechanical elements, but not the deeper meaning.

Which brings me to the issue of games as art. After listening to all the game creators talk about how much their games reflect themselves, how the games express what they think and feel, I don't know how how anyone could say that games can't be art. If you aren't yet convinced yourself, watch the movie and listen for those moments.

Overall, I definitely recommend this movie, and hope more like it will be made to show a variety of indie game creation experiences.

I thought that this documentary was really well done. The filmmakers did a great job of finding a good story with tension and drama in the development process. I felt such relief when good things finally happened to each of them.

The elation experienced particularly by the Super Meat Boy creators got me thinking: what happens to those who spend a few hellish years trying to finish their masterpiece, but end up with little to show for it? I wonder how often the risks pay off? I'm sure not everyone drops everything to work on their game, and even those that do probably don't always forego any sort of life balance to do it. But I would not want to see anyone experience risking everything and losing.

Of course, great success doesn't always bring happiness. Braid's creator was shown to be fairly (even deeply) disappointed even after his game broke indie records. People loved his game, but they didn't get it. The reviews focused on superficial mechanical elements, but not the deeper meaning.

Which brings me to the issue of games as art. After listening to all the game creators talk about how much their games reflect themselves, how the games express what they think and feel, I don't know how how anyone could say that games can't be art. If you aren't yet convinced yourself, watch the movie and listen for those moments.

Overall, I definitely recommend this movie, and hope more like it will be made to show a variety of indie game creation experiences.

Friday, November 9, 2012

Seeking Nominations for the 2013 Women of Vision Awards

I serve on the Advisory Board of the Anita Borg Institute, an organization focused on increasing women's participation in the technology workforce --- as technologists, and as technical leaders. One important aspect of our work is recognizing the contributions of amazing women technical leaders all over the world. We do this through the Women of Vision program.

We are now accepting nominations for the 2013 Women of Vision awards.

We could greatly use your help identifying women who deserve recognition, and facilitating their nomination. These women are incredible achievers whose stories inspire us, and whose example can be held up as a role model for thousands of other technical women. A bit of background:

These awards recognize outstanding women for Leadership, Social Impact, and Innovation. See the full descriptions of these award categories online.

Last year we honoured these amazing women:

Please think about a woman at your organization or school (or anywhere, really) who deserves to be honoured for her career achievements, and nominate her! Please contact me if there is any way I can help you with this action.

The deadline to submit a nomination is December 14, 2012.

Also be sure to save the date for the 8th annual Women of Vision Awards Banquet on May 9, 2013 in Santa Clara, California. Registration passes and table sponsorships will be available for purchase soon.

We are now accepting nominations for the 2013 Women of Vision awards.

We could greatly use your help identifying women who deserve recognition, and facilitating their nomination. These women are incredible achievers whose stories inspire us, and whose example can be held up as a role model for thousands of other technical women. A bit of background:

These awards recognize outstanding women for Leadership, Social Impact, and Innovation. See the full descriptions of these award categories online.

Last year we honoured these amazing women:

- Sarita Adve, Professor of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for Innovation.

- Sarah Revi Sterling, Faculty Director, ATLAS Institute at the University of Colorado at Boulder, for Social Impact.

- Jennifer Chayes, Distinguished Scientist and Managing Director, Microsoft Research New England, for Leadership.

Please think about a woman at your organization or school (or anywhere, really) who deserves to be honoured for her career achievements, and nominate her! Please contact me if there is any way I can help you with this action.

The deadline to submit a nomination is December 14, 2012.

Also be sure to save the date for the 8th annual Women of Vision Awards Banquet on May 9, 2013 in Santa Clara, California. Registration passes and table sponsorships will be available for purchase soon.

Thursday, November 8, 2012

#Turing for Christmas

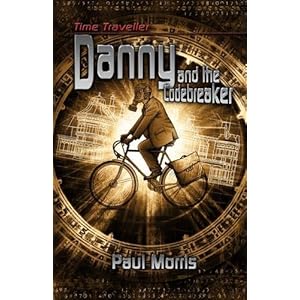

| As Christmas approaches perhaps you want to Turing theme your Christmas gifts. A new childrens book, by Paul Morris, has a Turing connection: "Time Traveller Danny and the Codebreaker." The book, which is part of the Time Traveller Kids series for 7 to 12 year olds, tells the story of Danny who goes back in time and meets Alan Turing. Paul carried out background research for the book using the archives at Sherborne School where Alan was a student from 1926 to 1931. Paul also has a family connection with Turing because his father, then a clerk in a Manchester firm of solicitors, witnessed the signing of Turing's will in February 1954. Thanks to The Alan Turing Year for this information. Tuesday, November 6, 2012A Bombe called “Auckland”

|